- Home

- Scott Kenemore

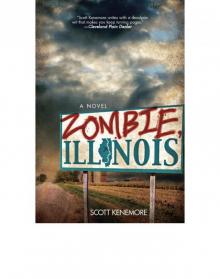

Zombie, Illinois

Zombie, Illinois Read online

PRAISE FOR SCOTT KENEMORE

AND ZOMBIE, ILLINOIS

“Scott Kenemore is a true rarity in speculative fiction—an unflinching chronicler of people and locales, his narrative eye relentlessly probes the depths of our vice and rejoices in our courage. And yes, he gives us zombies too. In fact, Kenemore writes zombies with an intelligence and depth of story that leaves most genre fiction—and certainly most zombie fiction—looking half-dressed in comparison. He’s really in a league of his own. When I read a Scott

Kenemore novel, I’m used to seeing great characters, great humor, and great action—those I’ve come to expect as par for his course—and yet with every book he writes he still manages to thrill me anew. And Zombie, Illinois is yet another high water mark in what is turning into a stunning career. What Carl Hiaasen did for the mystery genre, Scott Kenemore is doing for zombies. He’s that good.”

—Joe McKinney, Bram Stoker Award™-winning author of Flesh Eaters and Dead City

“Reliably pungent and profane.”

—P.F. Kluge, author of Eddie and the Cruisers and Dog Day Afternoon

“Scott Kenemore is the most original voice in zombie lit today, and Zombie, Illinois is his best book.”

—Matt Mogk, President of the Zombie Research Society (ZRS) and author of Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Zombies

“Terrific from cover to cover! Zombie, Illinois is a devious blend of sharp wit and shocking horror. Absolutely delicious!”

—Jonathan Maberry, New York Times best-selling author of Dead of Night and Rot & Ruin

“Kenemore gets Chicago as much as he gets the undead. Zombie, Illinois blends zombies into the Windy City’s corruption, politics, and blues like the filling in a delicious Chicago hot dog. The fourth star on Chicago’s flag belongs to the walking dead.”

—Aaron Sagers, CNN

Scott Kenemore writes with a deadpan wit that makes you keep turning pages.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer

ZOMBIE, ILLINOIS

A NOVEL

Scott Kenemore

Copyright © 2012 by Scott Kenemore

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected]

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of

Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kenemore, Scott.

Zombie, Illinois : a novel / Scott Kenemore.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61608-885-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Zombies—Fiction. 2. Chicago (Ill.)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3611.E545Z64 2012

813’.6--dc23

2012017903

eISBN: 978-1-62087-859-0

Printed in the United States of America

For Delia, a fine Illinoisan

Avaunt! and quit my sight! let the earth hide thee!

Thy bones are marrowless, thy blood is cold;

Thou hast no speculation in those eyes

Which thou dost glare with!

-Macbeth (III, iv)

Chicago is a bare, bleak, hideous city.

—H.P Lovecraft to Frank Belknap Long

Ben Bennington

Political Reporter

Brain’s Chicago Business

The flag ofChicago has four stars on it: one for political corruption, one for high taxes, one for racial segregation, and one for...

Damn.

I think it’s gang crime, but I’m not 100 percent sure.

Chicagoans always forget that last one.

My name is Ben Bennington, and I work for—don’t laugh— Brain’s Chicago Business.

Founded by publisher John Honeycutt Brain in 1973, Brain’s Chicago Business is the leading source ofbusiness news for companies in the greater Chicago area. Now with weekly print and online editions, Brain’s provides not only the cutting-edge industry news that our readers expect, but also award-winning themed issues like “30 Under 30,” “Who’s Who in Chicago Business,” and, of course, “CEOs Making a Difference.”

I’m a political reporter. (Politics and business are nowhere more intertwined than in Chicago—at least nowhere in the first world.) I’m a political reporter in a town that loves corrupt politicians. I mean loves them. Really loves them. Loves to hear them accepting a bribe on an FBI wiretap; loves to see photos of them associating with Italian mobsters or black gangbangers or the Chinatown mafia; loves to watch as they’re led away handcuffed. And loves—above all—to believe them when they swear they’ll never do it again. It occupies much of the local television news, yes, but Chicagoans also love to read about it—in the Tribune, Sun-Times, and, of course, in Brain’s. That’s where I come in.

You move to Chicago, and you think: How can a whole city behave this way? How can they enjoy this corruption, like it’s a sport or game? It’s not a sport or game, it’s bribery and grift and graft. It’s what everybody, everywhere knows is wrong.

And then you live here a little while and you slowly realize: Oh . . . it’s not that Chicagoans enjoy it; it’s not that at all.

Instead, it’s a defense mechanism against having their hearts broken and torn from their chests every few months by yet another crooked politician. It’s a hedge against their faith in humanity being reduced to a tiny nub by an endless series of betrayals. Because, when you believe in somebody enough to entrust them with your city—your home, the place you may have lived your whole life—and they sell you out at the first opportunity—and I mean the very first opportunity—you can do one of two things.

You can let your heart break and cry, “How could they?” (This option is painful, and most people can’t stand to do it more than once or twice.)

Or you can choose the other option: You can distance yourself from it all. You can be bemused and act like it’s all a big game. You can say, “That’s Chicago for you” (This option makes you cynical, true, but it also allows life to go on. It allows the citizens—and the city itself—to continue to function, even in the face of mass corruption. Accordingly, it is the option Chicagoans overwhelmingly select.)

So when an Alderman takes a $10,000 bribe to re-zone her district for a developer, or the mayor gives his cousin an $80,000-a-year job as an elevator safety inspector (who somehow never gets around to inspecting any elevators), or the governor tries to sell a vacated senate seat when the senator becomes President of the United States—Chicagoans treat it like a game. The political news reads more like the sports page. Veteran reporters in fedoras and suspenders act unsurprised as they compare the current generation of scoundrels to the previous one, and then to the one before that.

And I’m supposed to be one of those reporters.

I have the fedora. (A nice, $500 Optimo, though I usually don’t wear it.)

I have some suspenders. (Not so nice. From Kohl’s. Also seldom worn.)

But fuck me, because I am not a Chicagoan, and I do not have that ability to treat it all as a joke.

I’ve lived in this city for twenty years, but I spent eighteen before that growing up

in Iowa. And despite my many successful assimilations to Windy City life,1 I have yet to make that one crucial crossover that will allow me to believe that politicians stealing from the people they’re supposed to serve is funny.

Professionally and officially, I am as amused as the next reporter by the rampant corruption that pervades every ward. (I’ve got to keep my job, after all.) I adopt the “there they go again” attitude. At press events, I shake hands and mingle with these politicians—these criminal aldermen (and women) who comprise our city council. We joke and laugh convivially. We never mention that some of them—even, perhaps, most of them—will one day fall from their perches in some form of scandal. Many of them will serve prison sentences. Some of those will be lengthy. (Since I’ve lived here, a Chicago alderman has been convicted of a felony every eighteen months or so, and those are just the ones that get caught! [It gets worse the higher up you go. Four of the last seven Illinois governors have felony convictions.])

But for the city to continue to function—to “work” as they say—we must, all of us, play this game. I must ask about their families, new projects in their wards, and their opinions of the Cubs’ latest trade. Secretly though, I am disgusted with these people who use “clout” as a verb. (As in, “I clouted my way out of that one.”) I feel like this is not a game. Like their corruptions and bribes and associations with gangsters are not funny. Like instead, they are a shame . . . a horrible, wince-inducing shame. Watching Chicago aldermen glad-hand and smile at city events is like watching fashion models who are ugly and weigh 400 pounds but expect to be complimented on their pleasing features and toned physiques.

If I know anything, it’s that the men and women who run this town are not real leaders. If real leadership were needed, this city would fall. Our politicians would fail us utterly. Their sinecured appointees would prove useless. Their boring speeches would inspire no one.

I spend my days longing to see Chicago face some real test or trial that will expose these people for who and what they actually are.

I long for a crisis. For a disaster. For an invasion.

Pastor Leopold Mack

The Church of Heaven’s God

in Christ Lord Jesus

It is the Book of Proverbs, I think, that most astutely describes the sin of adultery.

In the seventh chapter, we meet the harlot who has perfumed her bed with “myrrh, aloes, and cinnamon” and invites the stranger into her room to spend the night in lust. In verse eighteen, she entreats him: “Come, let us take our fill of love until the morning; let us solace ourselves with loves.”

Solace.

That’s an important word.

It’s what the man in the Bible story is trying to find when he elects to sleep with a prostitute. It’s also the thing my congregation on the south side of Chicago is looking for. And it is the one thing I cannot give them.

My congregants . . .

They are beset on all sides.

Firstly, they are poor. The good book says the poor will always be with us—and that’s a point which, in a larger, philosophical sense, I wouldn’t presume to dispute—but the culture of poverty that has persisted for generations in my parish (our neighborhood is called South Shore) is frustrating, because it feels so unnecessary and arbitrary—as if a few small changes could correct everything and set our residents back on the right track. Why can’t my congregants make these few, small changes? Why can’t I help them do it?

I ask myself these questions every day.

During this recession, unemployment in our neighborhoods officially hovers close to 30 percent. When I drive down the street and see so many idle young men chatting and selling cigarettes and DVDs to one another, I’m convinced it must be higher. Like 50 percent.

In my neighborhood, less than half of the high school students graduate. Of those, almost none are prepared for college. One year, a valedictorian from the neighborhood went on to a city college and flunked out her first semester. And you say, okay, she wasn’t prepared. I can accept that. But she was the valedictorian. She was the best the school had. Something is definitely wrong here.

(This is where you say “Amen,” by the way.)

With the girls, teen pregnancy is unacceptably common. Almost no babies are planned. With the boys, a culture of violence pervades. There are shootings nearly every day. In the summer months, the fatalities over a long weekend can stretch into the double digits. Statistically, it is safer to be a soldier in the U.S. Army stationed in Afghanistan than it is to be a young black man on the south side of Chicago.

The billboards in my neighborhood are for cognac and AIDS medicine.

Something is wrong here.

And now, the darkest detail...

My neighborhood is not the worst.

My neighborhood is nowhere near the worst.

White folks from the north side of Chicago—who never bother to visit us—view “the south side” as one uniformly harrowing and dangerous place where they must remember never to go. They close it off in their minds. It becomes almost mythological—a world they only hear about on the nightly news. But if they ever scratched the surface, they’d see that “the south side of Chicago” is a dynamic mix of about thirty neighborhoods, each with a distinct personality and character.

South Shore, Chatham, Back of the Yards, Kenwood, Auburn-Gresham, South Chicago, East Chicago, Pullman, Grand Crossing—all these neighborhoods are slightly different. “Better” and “worse” in some ways, yes, but also distinctive and uniquely colorful. This one has a vibrant community of immigrants from Senegal. That one is renowned for its block safety clubs and high school football tradition. This one has been the epicenter of black newspaper publishing for eighty years. That one has the finest soul food in Chicago, if not the world.

And yet, to the outsider.we are all “the south side.”

Do we let that bother us? No, we don’t. We cannot afford to. We—ladies and gentlemen—have more important things to do.

(“Amen” also goes there. Thank you.)

I’m taking a trip now, and I want you to come with me.

I said my congregation is beset on all sides.. Let’s see for ourselves.I’m going to pull my Chrysler 300 (yes, a big ostentatious “preacher car”) out of the parking lot of The Church of Heaven’s God in Christ Lord Jesus—a crumbling structure built in the 1920s that needs a new pipe organ and a new roof—and I’m going to head south, toward Indiana. We’ll drive down roads called 12 and 41, parts of a lost highway named for General Grant.

As we drive, we will pass fish fry shacks, hot dog stands, dilapidated no-name hamburger joints, and Chinese restaurants that still advertise chop suey. What we won’t pass are grocery stores. These neighborhoods are what sociologists call “food deserts.” There are almost no businesses selling fresh produce. There’s one grocery store chain in South Shore. One brand-name grocery store for a neighborhood of almost 50,000 people. Think about that. I don’t even know if the store is profitable. Leakage—people stealing stuff—has to be through the roof. I think the franchise just keeps the doors open as a PR move, so in their TV commercials they can say that they’re “committed to all of Chicago’s communities.”

So no, not many options for fruit and vegetables and whole grains. But fast-food that tastes motherfucking delicious (if you’ll pardon my language)? Welcome to a fried grease wonderland!

Of course, this food isn’t good for you (not to eat all the time, which is what most people do). It gives our communities the highest rates of diabetes and high blood pressure in the city. But it’s affordable, and it tastes good. Most importantly, it provides—to quote the prostitute in the Book of Proverbs—solace.

For a lot of people around here, food is the most affordable kind of solace. It’s what they’ve got when they want to feel better.

A close second—as the astute reader will have already guessed—is alcohol, the last great legal vice (until, that is, we cross the border into Indiana.but more about that in a mome

nt).

Dave Chappelle has a comedy bit about driving in the ghetto and how the businesses go “liquor store, liquor store, gun store, liquor store.” But Chicago’s strict handgun laws have arranged things such that the places where you can purchase a functioning firearm—and they are legion—can’t exactly put up a sign. Consequently, on our ride, the businesses simply go “liquor store, liquor store, liquor store.”

At the end of nearly every block, a crumbling “packaged goods” establishment is making 90 percent of its money from liquor and beer sales. And liquor and beer—say it with me—are solace. They take away the pain. They are a short-term solution, but a solution nonetheless.

This is what I’m up against. This is what my congregation is up against.

(“Amen” goes there, too. Hallelujah.)

Moving on, we pass into a neighborhood called South Chicago. Here we find illegal bars, derelict houses—tax delinquent and/or victims of mortgage fraud—and abandoned apartment blocks filled with squatters. We also find places to buy drugs.

And, I hate to say it, but drugs are one of the few vices that are not an overriding problem for my congregation, as least, not directly. Nobody sitting in my pews is smoking crack or shooting horse, but most people have somebody in their family who is lost to drugs. Parents with kids who won’t behave worry that drugs are in that child’s future, and unfortunately, they’re probably right. Most certainly, drugs fuel the gang violence that pervades our neighborhoods.

But the people who actually make it into the pews on Sunday are, themselves, not usually on drugs. This is good. This is, as I remind myself, a start. I take encouragement from it because I must take encouragement anywhere I can.

(“Amen” definitely goes there.)

As we draw nearer to the Indiana state line, we begin to pass large swaths of undeveloped land owned by the park district. These swaths extend eastward and eventually border Lake Michigan. They are full of nothing—bleak and littered with garbage. They are lonely places, giving off the feeling of having been forgotten. Developers don’t want to build here, and the city’s park system has a shrinking budget and more pressing issues. The politicians would like to see these swaths built up—probably because wealthy people can see them from their boats out on Lake Michigan and are depressed by the sight. (These politicians—for what it’s worth—have not voiced much concern for the urban neighborhoods adjacent to these nautically visible swaths.) The city’s latest bright idea has been to use them to stage a three-day rock music festival every summer, featuring bands tending to the tastes of white fraternity members. Will this project, in any sense of the word, “work?” I do not choose to dignify that question with a response. For now, we drive on past these lonely brownfields where, 362 days of the year, local kids go looking for trouble, drunks pass out, and drug deals go down.

Lake of Darkness

Lake of Darkness The Zen of Zombie

The Zen of Zombie Zen Of Zombie (Zen of Zombie Series)

Zen Of Zombie (Zen of Zombie Series) The Ultimate Book of Zombie Warfare and Survival

The Ultimate Book of Zombie Warfare and Survival Zombie-in-Chief

Zombie-in-Chief Zombie, Ohio

Zombie, Ohio Zombie, Illinois

Zombie, Illinois Zombie, Indiana

Zombie, Indiana