- Home

- Scott Kenemore

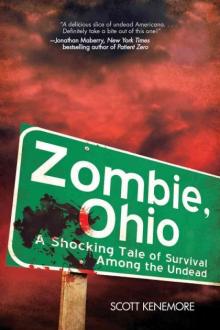

Zombie, Ohio

Zombie, Ohio Read online

Scott Kenemore

One forgets that one is a dead man conversing with dead men.

-J. L. Borges, "There are More Things"

For Heather, the Kenemores, the Blissters, the Cougars, and Mr: T. Banks

Hello.

I want to eat your brain.

Well, not your brain, necessarily. It could be anybody's brain.

I mean, let's be clear ... Nothing about this is personal.

But ... brains. Yes. I do want to eat brains.

Brains ...

Braaaaaaaaains ...

Sorry. You'll have to excuse me. I ... drift a little bit sometimes. These days, it just sort of happens, and I can't control it.

Don't let it worry you if I ... list ... on occasion. You're still doing fine, and I'm not losing interest. I'm certainly not feeling sick. Okay, to be completely honest with you, I do feel a little sick. But I always feel a little sick. I'll be fine. It's not like I'm going to die or anything.

I don't think I can.

So-what did you want to know about?

Really?

You're serious? You want to know about that?

All right, I'll tell you ... sure.

Just give me a moment to ... collect myself.

I remember waking up ... or something ... by the side of the road, near a town I would later learn was Gant, Ohio. It was midwinter. My eyes were closed as I came to, but I could tell it was winter. I could smell it.

And I ... I opened my eyes and I saw the sky-a bleak gray and white Midwestern sky-and it was snowing just a little. Light, tentative flakes that drifted down absently.

I was on my back. My legs were crossed awkwardly, one atop the other, and my arms were spread out wide.

I untangled my legs slowly and sat up, pushing myself upward on numb, empty-feeling arms. I looked around and saw the trees and the road-empty winter woods, and a lonely country highway without streetlights. On the other side of the road was a wrecked car, impaled squarely against an old, gnarled buckeye tree that split into a "V" halfway up. One of the front tires on the car was still spinning. The headlights were on, and there was a massive, violent hole in the front windshield, like someone had been thrown through it.

I looked at it, and I looked at me. And I thought that maybe I was that someone.

I stood up slowly, feeling like a person who has been asleep for days. Like a patient coming out of anesthesia. Dizzy and lightheaded, but also empty. A lingering emptiness that felt like it would soon give way like I was waiting to come back and feel like myself again after a sickness ... get an appetite, and so forth. (Probably, I thought, this was shock, and what awaited me when it wore off was horrible pain.)

I took a step. It was okay. Not normal, but I could work with it. I took another. Walking felt like floating. It was awkward, but I could do it. I took another step, and then another.

I looked down at the road. Gray asphalt covered with snow so thin it blew in the wind. The sky above the bare, reddish-brown trees was getting dark. It was a late afternoon in winter.

It was also eerily quiet. No traffic and no people sounds. It felt like Christmas Eve, or some other holiday where everybody is at home. Slowly and carefully, I crossed the road and made my way over to the car. Not because I knew whose car it was-mine or someone else's-or because I wanted anything from it. Rather, I walked toward it because it was what there was. The headlights were like a beacon beside the lonely country road in the creeping dusk.

I walked gingerly, like a man with a hangover-trying not to provoke a throb or an ache. I looked myself over as I did. There was a little blood on my hands-a few cuts, but they weren't bad. The rest of my body seemed okay. I wore a jacket, a red-andblack-plaid shirt, and some jeans. The jeans were wet and clingy from snow.

I crept closer to the car.

It was a tiny import-a convertible with its flimsy canvas top raised heroically against the Ohio winter chill (and now ripped apart in several places from the accident). This was the kind of car that wouldn't have an airbag, I thought. The kind of car that invincible-feeling men tend to drive too fast down winter roads. The kind of car that, if you crashed it you were pretty much just going to be fucked (and maybe that was a perverse part of the appeal).

I moved closer, easing my way down the embankment to where the automobile rested. I could hear the radio or a CD playing through the shattered windshield. It was a classic rock song. I'd heard it many times before ("Oh yeah, that old number ..."), and yet I couldn't place the artist or title.

Something about this inability to remember the name of the song really unnerved me. You know, like when you can picture someone's face, but just can't think of his name? What the fuck, right? It's crazy. And it was like that with this classic rock song. It seemed crazy that I couldn't think of it. Insane.

But I know this song, I thought to myself. Of course I did ... Yet hard as I tried, I couldn't name it.

I just couldn't.

Keep in mind that I knew as much then as you do right now about where I was and what was happening to me. (You know more, actually. I didn't even know I was in Ohio, near a small college town called Gant.) Anyhow, that was when it hit me.

Amnesia. This must be amnesia.

I must be the man who went through that windshield, and this must be amnesia.

The driver's license was buried deep in the folds of the thick brown wallet I found in the back pocket of my jeans.

The name on the license was Peter Mellor. Though it listed a birth date, I couldn't pin down an age because I couldn't seem to remember what year it was. In the photo, he looked early fortyish, probably of Irish descent, with moppish brown hair and a drinker's redness to his cheeks. There were the beginnings of lines on his brow and circles under his eyes, but the face still had the confident jaw and steely eyes of a healthy man. In the right light, I suppose he might have looked handsome. In the right light ...

The weight was listed as 175. Looking down at the bulge above my belt, I guessed this was being a bit generous. But was this, was he ... really me?

I crept over to one of the car's side-view mirrors and woozily knelt down in front of it. In the dying light, I stared hard at the face it showed me. The visage I beheld looked fatter and more haggard than the one in the picture. The cheeks and nose even redder. The lines crossing the face even deeper.

But, yes. It was the same face. I was ... apparently ... Peter Mellor.

And Peter Mellor (said the State of Ohio Department of Motor Vehicles) lived at 313 Wiggum Street, in a place called Gant, Ohio. Zip code 43022. Well, fuck, I thought. Okay. So we've got that much. Not a lot, but something to start with.

And then another thought: Wiggum-like the incompetent, round cop on The Simpsons. The Simpsons-that TV show I like to watch! Yes, it was coming back. But when did I watch it? And where? I couldn't remember, but it seemed I was unable to think of this street name without thinking of the porcine, Edward G. Robinson-sounding policeman each time that I did. They were connected in my mind, now as then. I was remembering some things, I realized.

I patted myself down and found a cell phone in my right front pocket. I opened it. It felt familiar, like Wiggum Street, but the names saved in the phone's memory did not.

Jeeps.

Sam.

Mo.

Harvey.

I had no clue who these people were or who the phone would call if I clicked on one of their names. For a moment, I thought about dialing 911. (That was the emergency number; I hadn't forgotten that.) But what would I say? Where would I say that I was? I turned the phone off and put it back in my pocket.

Keys, I thought. That's what's missing. The third thing. I should have a wallet, cell phone, and keys. After some looking, I found them in the ignition of the car. I

pulled the keys out (which also, finally, killed the radio) and shoved them into my right front pocket, where they felt familiar. At home.

Then, as I stepped back to close the car door, I saw the gun. It was on the floorboard, next to the gas and the brake. Maybe it had been secured when I'd been driving, and had only rattled loose after I'd gone into the tree. Maybe it had been in my pocket and had fallen out in the crash. Or maybe I always kept a gun next to the gas and brake pedals.

I stared at it fora long time, like I was trying to figure out what it was. Which was silly, of course, because I knew exactly what it was-a loaded revolver with a walnut handle. Cold blue metal. Heavy and new-looking. I had to admit, even then, in my dazed and unsure state, that the thing looked pretty cool.

For a second I wondered, "Am I the kind of guy who always keeps a loaded gun tucked in his car somewhere? One of those guys? A dude who has to pack heat when he's just going to the grocery store or picking up the dry cleaning?"

It didn't feel like I was. No, I felt more like the kind of guy who would only carry a gun if he had a reason for it. A really good reason. I decided that if I had a good reason to have a gun when I crashed my car into a tree, I probably still had a good reason now. I tucked the gun into my waistband and pulled my shirt down over it.

As I was doing so, I finally heard a sound that was not the snow falling on the winter road or the wind in the trees. It was an approaching engine.

Approaching fast.

By the time I looked up from tucking in the gun, it was already whizzing by. An ancient Ford pickup-the driver, an older man in overalls, wild and mean-looking-rocketed down the rural highway past me. A shotgun was propped next to him, and he gripped it with his free hand as he drove. He was speeding-going very fast considering the snow, I thought. As he passed (without slowing even slightly), he looked first at the wrecked imported car, and then at me-our eyes meeting for just an instant. His stare was cold and intense. Anxious, too-like he was running from something. Or to it.

I turned dumbly and watched the truck as it sped away, the taillights shrinking to ocher balls. I listened as the timeworn engine slowly faded into the distance. Then nothing. Just the snow and the wind in the trees.

That was when I decided I should start walking. Start walking and see what I found like a hospital, or a clinic-hell, at that point I'd have taken a large-animal vet. Just someone in a white coat to tell me what was wrong with me. Tell me what was happening and who and where I was. I reasoned that if I walked, I might encounter familiar sights that would jog my memory.

Sure, I could sit by the car and wait for a passerby who might be inclined to stop, but the shadows were growing long and the temperature had to be dropping. I was still in shock from the wreck-that was why I didn't feel cold, of course-but it had to be 30 degrees out here. I knew I should seek shelter soon. Preferably someplace warm, with people.

Just as I was having that thought, I spied a simple black knit cap stuck to the side of the bifurcated tree, right where the car had hit. Was it mine, I wondered; did it come off my head when I went through the windshield? I walked over and plucked it from the frozen bark. Sure enough, the texture felt familiar. Warm. Comforting.

Pulling the black cap down over my ears (which, I noticed, were a little numb), I made my way back to the shoulder of the road, and faced west-presumably the direction from which I had been driving.

Then I did something that zombies have always done, since the beginning of time-something deep and innate which the undead have always been driven to do.

I started walking ... in search of people.

Kenton College.

A quick search of the Internet will tell you all about it. (They groom a nice Wikipedia page.) It's a small, selective liberal arts school, set atop a hill in rural Ohio. Sizable endowment. Politically liberal, but with token conservatives sprinkled throughout. Trends upper-middle class. (Tuition is obscene. More than most people make in a year.) Its well-manicured campus has beautiful neo-Gothic humanities buildings, ultramodern science and athletic facilities, and dingy but venerable fraternity lodges that lurk in dark places. Kenton also has three or four very famous faculty members. (Or maybe used-to-be-very-famous faculty members.)

When you work there, most days it feels like you're playing for a really good AAA baseball team. Not the big leagues, sure, but you could do a lot worse. Then, other days, when a project goes well or somebody gets a little recognition in the New York Times, you feel better about it like yeah, maybe you are in the majors, and even a pennant chase seems possible.

And unless you're a student, the community at Kenton feels almost incestuously insular. Everybody gets to know everybody's business. (It is, technically speaking, just a small town in a rural part of the state.) The grounds are a quiet, tranquil place, especially when the students aren't around. For many, it's far too quiet.

And that's just how it was as I approached Kenton on that dark and snowy evening. I had been walking west along the shoulder of the two-lane highway for perhaps five minutes, and the sun had nearly set. It was as silent and still as an empty movie set. No traffic passed me, and I saw no one. Then, suddenly, I found myself standing in front of the long drive heading up the hill from the highway to the college. The large Kenton College seal, affixed (somewhat gaudily, I thought) to a boulder at the base of the hill, loomed above me. I walked right up to it.

This seal is normally illuminated, I thought to myself. Lit up by decadently expensive spotlights from below. Even in the middle of the night. Even during holidays and vacations. They always keep it lit. (I didn't know how I knew this, but I did.) But it wasn't lit now. Something was wrong. The seal was dark. Almost everything was dark. Up the hill, I could see only one or two lights. I knew there should be many more.

Maybe, I thought, up this hill is the way to Wiggtun Street and the address where I live. Maybe seeing it will help me remember. I straightened my black knit hat and started slowly up the steep incline toward the college. After a minute of walking, I thought I saw movement in the darkness above me. As I drew closer, I made out the silhouette of a man holding a rifle. He had stopped and was looking at me. Waiting for me.

I kept walking toward him. (What else could I do?)

As 1 -neared the top of the hill, I began to discern the small college town unfolding behind this man. ("Village" might be a better word, actually. Again, see their Wikipedia page. Gant, Ohio: population two thousand-if you count the one thousand five hundred students.) From my position at the edge of the hilltop I could see small, dark houses, humorless administrative-looking buildings, and one or two cars. The entire campus was silent as the grave. Empty, as far as I could tell ... except for this man and his rifle. I drew close enough to make out his face in the growing darkness. He was black, middle-aged, and wore a thick mustache. On the breast of his puffy, blue jacket was emblazoned KENTON COLLEGE SECURITY. There was still a little sun left around the edges of the sky, but he drew a flashlight and shined it right in my face when I got close. Then he lowered it and smiled.

"All right then, Professor Mellor," he said genially. "You keeping it safe out here?"

"Uh, yeah," I said.

I had not spoken since awakening after the accident, and it suddenly seemed my throat was very dry. I could not remember what my voice usually sounded like, but my response to the guard felt guttural and hoarse.

"Good to hear," he said, as if he did not quite believe me. "Professor Puckett, Dr. Bowles, and I-we're keeping the watch on the graveyard tonight. You let us know if you need anything."

For a moment I hesitated.

This man, whoever he was, clearly knew who I was. It was enough to make me jealous. Part of me wanted to scream: "Yeah, I need something. I need somebody to tell me who I fucking am!" I wanted to shake him by the shoulders until he told me.

But something else told me that this was not the right thing to do. Not now. Not yet. Not until I knew more ... It was clearwhoever I was and wherever I was-that somethi

ng was going on. Something bad. There was this pervasive ... vibe I was getting from everything around me. And it wasn't a good vibe. It was a profoundly, profoundly nasty one. I had stumbled into the middle of wrongness. Something had disturbed this place. This world. I could see it in the guard's eyes. Behind the courtesy and the forced smile, there were other things. Wariness. Weariness. Fear.

And now every part of my psyche told me that I needed to find out what this wrongness was without betraying that I hadn't a clue what was happening.

"Okay, thanks," I told him. "I'll see you later on."

Over the guard's shoulder, I spied a green street sign, just visible in the dying light. It said WIGGUM STREET. What were the chances?

The guard shouldered his weapon and moved on, giving me one final, skeptical glance. I waved at him and made my way over to Wiggum Street.

Professor Mellor.

That was what the guard had called me.

Well then, I thought ... so I'm a college professor. And being a college professor is good, right? Probably beats being the college janitor. You get jackets with elbow patches and tasteful suspenders and so forth.

What did I teach? I wondered. Did I have tenure? Were my classes popular with the students, or merely something they endured? I thought again about the face I'd seen on Peter Mellor's driver's license, and tried to picture it at a lectern. It wasn't easy to do.

I entered Wiggum Street slowly and cautiously, gingerly creeping deeper and deeper into what I can only call a ghost town. Houses with dark windows. Shuttered, padlocked dormitories. Empty parking lots and empty driveways. My only companions were a pair of stray dogs that trotted about gleefully, like thieves given the run of the town. I suddenly wished I had a flashlight. It was very hard to make out anything, much less the house numbers.

At the very end of the block was a shabby, two-level home with a gambrel roof like a barn. It was one of the only places with any lights on at all. I felt like they had probably been left on absently, and that this might be a typical oversight. A generator hummed fitfully from somewhere inside. As I neared it, I felt increasingly like it was going to be number 313. My house.

Lake of Darkness

Lake of Darkness The Zen of Zombie

The Zen of Zombie Zen Of Zombie (Zen of Zombie Series)

Zen Of Zombie (Zen of Zombie Series) The Ultimate Book of Zombie Warfare and Survival

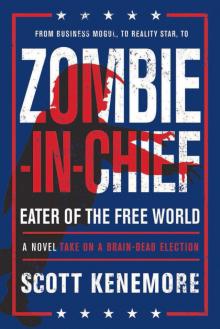

The Ultimate Book of Zombie Warfare and Survival Zombie-in-Chief

Zombie-in-Chief Zombie, Ohio

Zombie, Ohio Zombie, Illinois

Zombie, Illinois Zombie, Indiana

Zombie, Indiana